Transports

345657298

San Esteban Port

340487843

Santa Bárbara Mine

The company Sociedad General de Ferrocarriles Vasco-Asturiana, popularly known as Vasco Asturiano (Basque-Asturian), was born as the result of an effort made by the Biscayan iron and steel industry to speed up the transport of coal from the Caudal basin.

The company was constituted in 1899 and its objective was to build a metre-gauge railway linking Ujo with San Esteban de Pravia’s seaport, which was developed at the same time as the railway itself. Together with this main line, a railway branch was designed to connect Fuso de la Reina with Oviedo. The project was commissioned to the engineer Valentín Gorbeña, who also designed the stations. The works went ahead fast, which allowed its inauguration in 1908.

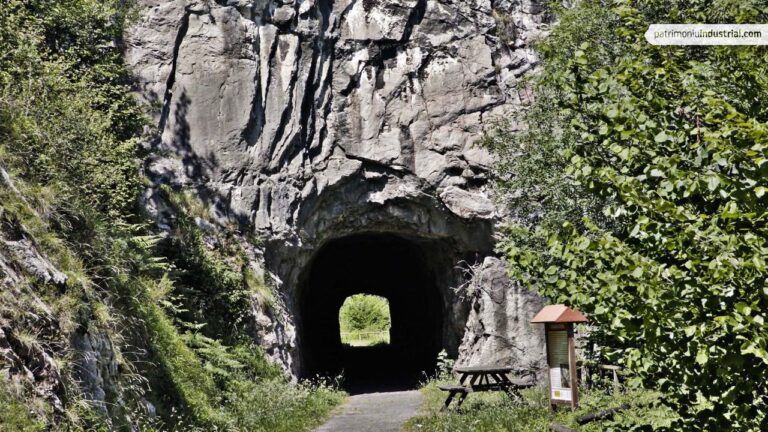

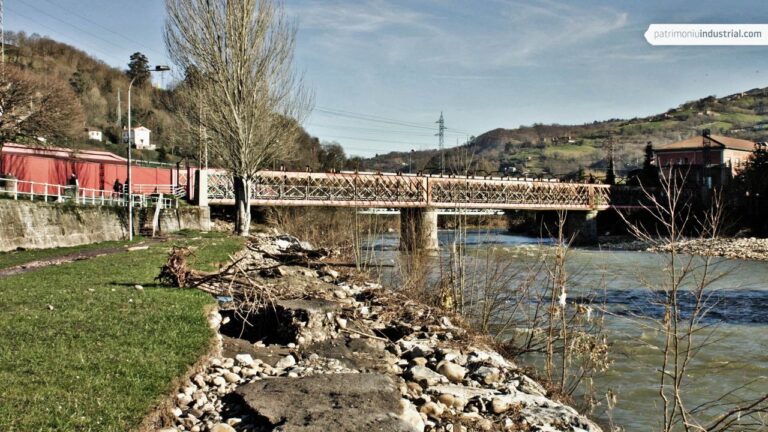

The outline of the route followed the course of the Caudal and Nalón rivers, and we could only find some counterslopes on the Oviedo railway branch. However, it was necessary to carry out a large number of masonry works, mainly tunnels (43 in total) and several metal bridges, which were provided by the Belgian industry. The original project was 81 kilometres long.

An enlargement up to the valley of the Aller river from Ujo to Collanzo (22 kilometres) was designed in the 1920s. It was completed in 1935 and included four tunnels and a concrete bridge.

For years, the Basque-Asturian was mainly a coal railway. This task was combined with a suburban service that connected the stations along its route with the capital city of the Principality of Asturias.

The private company period of the Basque-Asturian Railway ended in 1972 when it was nationalised by Feve. This change meant several changes which have been particularly significant in the last few years, such as the closure of the Fuso-Oviedo stretch, which has now become a greenway, and its replacement by a new access from Trubia. In addition, the Trubia-San Esteban stretch has been electrified and the commercial service from the first of these stations to Baíña has been eliminated.

Now that the coal transport has disappeared, it still provides passenger services. Its route preserves an interesting group of original masonry works, some of which are set in breath-taking landscapes.

Recent Comments