by Rubén Domínguez Rodríguez

B.A. in Art History and Postgraduate Work on Industrial Heritage Management (University of Oviedo). Reseach at Oviedo University, President of CEAG, codirector of the magazine Alfoz and Tutelage's Vowel of the Artistic-Historic Heritage at Aproha. His works are focused on research and dissemination of Cultural Heritage, especially, Industrial Heritage.

From the very beginning of industrialization until the expansion fostered by the National Industry Institute (INI) in the past century, companies have implemented very complex paternalistic policies, some them addressing housing.

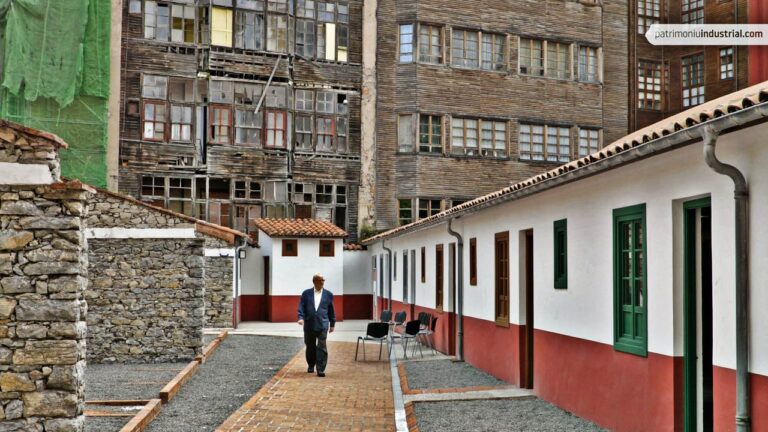

Ever since the dawn of industrialization in Asturias, marked by the creation of the Oviedo and Trubia weapons factories, workers’ housing has been a constant issue. Public and private companies alike from every industrial sector in Asturias have provided housing and services that vary according to the time period and the intentions of each company.

Industry was often born in unpopulated areas, which in addition to the migration movements of the period favours the creation of residential areas – even within factory premises – at its earliest stages of development. Paternalistic policies (including issues such as housing, leisure, services, and so on) have the single goal of keeping workers in a single location, and then foster a sense of wellbeing that should in turn have a positive impact on production.

Industrial development in Asturias has resulted in very different types of plants. From energy production companies such as Hidroeléctrica del Cantábrico (Hydro-Cantabrian Power Company) to steelworks such as ENSIDESA, they all have fostered the construction of housing developments. Some relevant examples are the settlements of A Paicega by the Grandas de Salime power plant and those by the Miranda power plant, in Belmonte County.

Their stylistic diversity ranges from the use of local features, as in Llaranes and Trubia, to the presence of elements revealing artistic aspirations, as in the residential area of Urquijo in La Felguera, by Enrique Rodríguez Bustelo, and the Soto de Ribera power plant settlement, by Ignacio Álvarez Castelao.

From historicism to rationalism, all these instances constitute a legacy worth preserving so as to understand the recent history of a region that designed these towns with the purpose of controlling the workers.

BOGAERTS MENÉNDEZ, J., El mundo social de ENSIDESA. Estado y paternalismo industrial (1950-1973), Ediciones Azucel, Avilés, 2000.

DOMÍNGUEZ RODRÍGUEZ, R, (coord.), Pulpitum. La historia de la enseñanza en Llaranes a través del mobiliario escolar, Club Popular de Cultura “Llaranes”, 2018.

DOMÍNGUEZ RODRÍGUEZ, R, “ENSIDESA y su mundo paralelo”, en VV.AA. Avilés en el pasado, Avilés, 2015.

DOMÍNGUEZ RODRÍGUEZ, R, Del progreso al estorbo. Errores y aciertos en la destrucción, intervención y divulgación del patrimonio industrial de Avilés (Asturias), Universidad de Oviedo, 2019.

GARCÍA LÓPEZ, M.E., Las Escuelas del Ave María de Arnao, Ayuntamiento de Castrillón, 2004.

TIELVE GARCÍA, N., “Company Towns: arquitectura y paternalismo. De la Compagnie Royale Asturienne des Mines a Cristalería Española”, Estoa. Revista de la Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo de la Universidad de Cuenca, 2018.

ZAPICO LÓPEZ, M., “La Nalona: un proyecto de poblado desaparecido en Langreo”, en ÁLVAREZ ARECES, M.A. (coord.), Patrimonio inmaterial e intangible: artefactos, objetos, saberes y memoria de la industria, INCUNA-CICEES, 2012, p. 391-397.

Recent Comments