by Faustino Suárez

B.A. and Ph.D. degrees in Geography and History (University of Oviedo). Vicepresident of INCUNA, Industrial Archeology Association. Research area: the geography of industrial heritage.

The rich coal supplies of Asturias were first mined at an industrial scale towards the end of the eighteenth century, yet this activity reached its full development in the second half of the following century.

Alejandro Aguado, 1st Marquess de las Marismas del Guadalquivir and a key figure in the industrialization process of Asturias during the nineteenth century, used to say “Where there is coal, there is everything.” There was coal in Asturias, indeed, as well as other essential industrial resources such as timber and water. These were the foundations that made possible the very first railroad built in the peninsula for industrial use, the Langreo-Gijón line. This railroad contributed to the establishment of the first large steelworks in the region at La Felguera, which in turn became the main incentive for coal mining using modern, capitalist-economy methods and techniques.

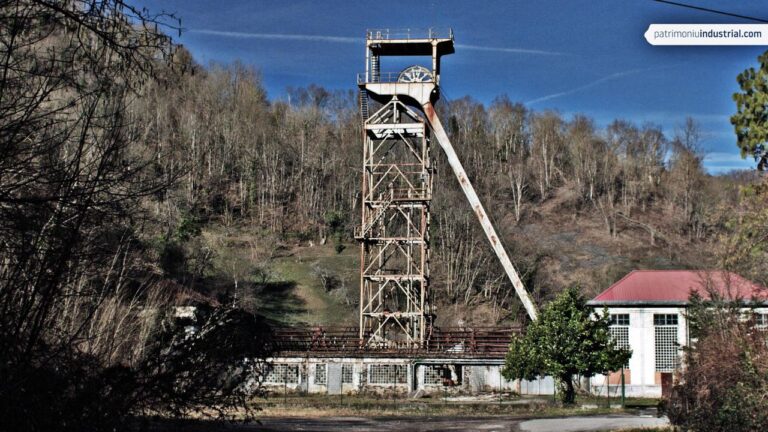

Even though the existence of abundant coal was well known since antiquity, and although local eighteenth century companies such as Reales Minas de Langreo (Langreo Royal Mines), Empresa del Nalón (Nalón Company), and Fábrica de Trubia (Trubia Factory) had pointed out the potential of the rich mineral supplies, coal mining bloomed in the second half of the nineteenth century, under a liberal system enabling the administrative and legal framework essential for the creation of a national industry. And yet, Asturian coal mining ultimately developed at a mass scale under very different circumstances: first during World War I, when the main European producers were involved in the fighting, and later on, in the context of the self-sufficient economy of Franco’s military dictatorship, when the mineral became irreplaceable. Some of the largest mining sites were built during these two periods, such as Sotón, María Luisa, San José, San Jorge, Polio… Mining-based development was not limited to the areas in question, and so appeared new settlements such as Solvay, Arnao, La Felguera, and Bustiello, a consequence of intensive social policies by both the companies and the government that still did not compensate for the low salaries and rough working conditions. In sum, today there is an invaluable Industrial Heritage in the region, and the derricks, veritable iron giants frozen in history, are the landmarks indicating the places where many generations of men and women lived, worked and produced coal for Spain.

ÁLVAREZ ARECES, M.A., El carbón, una Historia con historia, Hunosa, 1987.

ADARO RUIZ- FALCÓ, L. Datos y documentos para una historia minera e industrial de Asturias, t. III y IV, Suministros Adaro, 1981-1994.

COLL MARTÍN, S.; SUDRIÁ I TRIAI, C. El carbón en España, 1770-1961, Ediciones Turner, 1987.

OJEDA, G., Asturias en la industrialización española 1833-1907, Siglo XXI de España Editores, Madrid, 1985.

SUÁREZ ANTUÑA, F. Carbón para España. La organización de los espacios hulleros asturianos, XI Premio Padre Patac de investigación, Ayuntamiento de Gijón, Consejería de Cultura, Comunicación social y Turismo, KRK Ediciones, 2006.

SUÁREZ ANTUÑA, F. “Pozo Sotón”, en 100 elementos de Patrimonio Industrial en España, TICCIH-Instituto de Patrimonio Cultural de España, Madrid. 2011.

SUÁREZ ANTUÑA, F. Paisaje y Patrimonio. El Pozo Sotón (San Martín del Rey Aurelio), CICEES, Ayuntamiento de SMRA, 2012.

Recent Comments